Even Pantsers get writer’s block. Words won’t come, ideas won’t come, nothing comes but the vast white expanse of the page before you. It’s frustrating and may even seem like the words will never come again, like you’ve walked from a free-flowing fountain into the most arid of deserts, with no way back.

For me, writer’s block is often about overthinking when I go to write. What I suggest in such cases is finding a way to shut off whatever pre-emptive censor or editor is inhibiting your work. I’ve found a few strategies that help me achieve that end. Here they are:

- Freewriting. In his book, Writing Without Teachers, Peter Elbow

offers the approach he labels “freewriting”, where you simply put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard and write whatever thoughts come to mind for, say, 10-15 minutes. That means no stopping, no correcting, no editing, no censoring what comes out. Just put it all out there until that time is up. It won’t likely be pretty or polished, but in the rush of words there may come the idea or phrase that unblocks you.

offers the approach he labels “freewriting”, where you simply put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard and write whatever thoughts come to mind for, say, 10-15 minutes. That means no stopping, no correcting, no editing, no censoring what comes out. Just put it all out there until that time is up. It won’t likely be pretty or polished, but in the rush of words there may come the idea or phrase that unblocks you. - Cut-Ups and Fold-Ins. Cut-ups are exercises wherein you copy pages from books you adore, or even ones you don’t, and literally cut those pages to pieces with scissors, then toss them up in the air or shake them around in a bin of some sort so that the words become scrambled. When you look at the end-result you will find a lot of incoherent phrases, but you will likely also find little gems of ideas and phrases as the order of the words is sundered. Fold-ins are similar to cut-ups, except that instead of cutting pages to ribbons, you fold them next to or over one another, so that new meanings to familiar sentences are found. Both exercises are designed to remind you that language is malleable, and to change your relation to it. Both these strategies have been used by the Surrealists as well as William S. Burroughs,

who published whole books of cut-ups and fold-ins, such as The Ticket That Exploded.

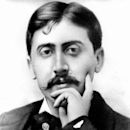

who published whole books of cut-ups and fold-ins, such as The Ticket That Exploded. - Change Your Habits. The simplest approach in the end, may be to change the time or location in which you write, if possible. Or change how you write, by switching from pen and paper to keyboard, or vice-versa. This again may jar loose whatever is binding your creativity. You may not be able to seal yourself in a cork-lined room like Marcel Proust

, but there are plenty of opportunities for writer’s retreats and such to offer a change of scenery. Switching up what you read may help too. Try reading in a different genre, or the work of an unfamiliar writer. Or, for example, if you read largely in fiction, switch to reading a nonfiction book, especially one outside your comfort zone. I mainly read fiction and find science difficult. But I’ve also found at times that by reading in science, the cross-pollination of ideas stimulates me to create my own work.

, but there are plenty of opportunities for writer’s retreats and such to offer a change of scenery. Switching up what you read may help too. Try reading in a different genre, or the work of an unfamiliar writer. Or, for example, if you read largely in fiction, switch to reading a nonfiction book, especially one outside your comfort zone. I mainly read fiction and find science difficult. But I’ve also found at times that by reading in science, the cross-pollination of ideas stimulates me to create my own work.

Not all these strategies will work for everyone. But they are options when being stuck for words feels faintly hellish.

I’ve also learned, as I’ve gotten older, that sometimes what seems to be writer’s block is just my creative forces telling me that they need time to regroup. I sit with the silence as something just as natural as any other aspect of my life. I have a sense within me now, unlike when I was younger, that the words and ideas will return and I will write once again when the time is right for it.

The other change of mind that I’ve had since growing older is that I treat all my writing as legitimate. I used to treat journaling as ancillary to my creative writing, which neglects the fact that journaling takes creative effort too, even in a journal as mundane as mine. I have a friend with whom I write actual physical letters, because we’re both old, and I can look at that now as another creative channel whereas I wouldn’t have seen it as such when I was younger.

In the end, writing is writing. If you’re putting words down in some manner or other, you’re writing. The whole seeming monolith of writer’s block is based on the idea that certain types of writing should be privileged over others, which is a fallacy. Again, writing is writing. I firmly believe that the only competition is with and within yourself. As soon as you acknowledge that words are words and thus mean you’re writing, the easier it becomes to endure what once would have been deemed writer’s block. I value some of my words over others, true, but that doesn’t mean that the rest are a waste or not writing. They took effort too. They took creativity. And they count as legitimate writing, plain and simple.

A last word: writers have a reputation for drinking alcohol and dabbling in other kinds of mind-altering substances. Those, I suppose, can also break through any sort of writer’s block. It’s an individual choice as to whether to do so or not.

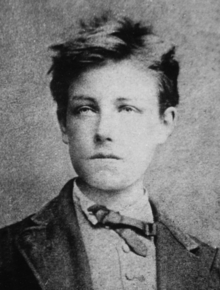

Arthur Rimbaud  wrote about the “deliberate derangement of the senses”. He approved of using substances like hashish and absinthe to achieve that aim.

wrote about the “deliberate derangement of the senses”. He approved of using substances like hashish and absinthe to achieve that aim.

Anna Kavan  wrote while addicted to heroin.

wrote while addicted to heroin.

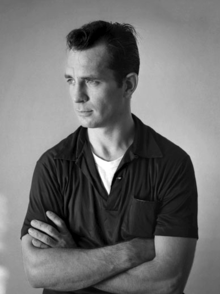

Jack Kerouac  was reputed to write on speed, among other substances.

was reputed to write on speed, among other substances.

The massive number of writers said to have written on alcohol led to the myth that all do.

I chose to dabble in liquor and drugs to release my creativity when I was very young. And I did write on those substances, quite prolifically. But lo, these many years later, I have kept very little of that writing. As I said earlier, it’s all valid as creative writing. I just don’t really care for most of it now. I don’t judge anyone who does write this way; it’s just not for me.

Leave a comment